Katherine "Kate" Lee Harris Adams

Originally published as "A North Carolina WASP"

by Sandra O. Boyd

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Fall 2003.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

Today, women can pilot commercial airliners and military planes, but not too long ago, they could not get such jobs. After the Wright brothers flew the first airplane, both men and women learned to fly, but women did not get as many chances to become pilots as men did.

Today, women can pilot commercial airliners and military planes, but not too long ago, they could not get such jobs. After the Wright brothers flew the first airplane, both men and women learned to fly, but women did not get as many chances to become pilots as men did.

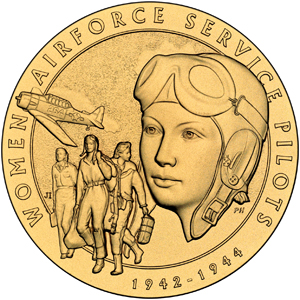

However, during World War II, one group of women did get to fly military planes. They were the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). One of these pilots, Katherine Lee Harris “Kate” Adams, was from Durham.

As a child, Adams had loved learning about anything having to do with aviation. While studying at Duke University, she got the chance to take a Civilian Pilot Training (CPT) course. Colleges and universities around the country offered CPT programs, but they accepted only one woman for every ten men. Adams “jumped at the chance” to take the class and drove from Durham to an airfield east of Raleigh to take the flying lessons. When she graduated from Duke in 1941, she had a degree in fine arts and a private pilot’s license.

That same year, Japan attacked the United States military base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, bringing the nation into World War II. Patriotic citizens wanted to know how they could aid our country. Women pilots wanted to use their flying experience to help the military, but at first the army rejected them. People criticized women for wanting to do a “man’s job.” However, the army needed pilots so desperately at the beginning of the war that it decided to allow women to fly military planes.

The WASP did many jobs for the military. They flew all types of planes, transporting them from United States factories to military bases around the country. Some WASP pilots towed targets behind planes so that soldiers could practice shooting at moving objects. They also risked their lives test-flying airplanes that had been damaged and repaired.

Kate Adams did not have enough flying hours to qualify for the first class of women who joined WASP. But when the program reduced the number of flying hours required, she was accepted. After training, she worked at Napier Field in Dothan, Alabama. She conducted solo flights to test AT-6 planes that had been repaired, and she ferried planes from Napier to other United States bases. Then she worked as an instructor for flight cadets.

The WASP at Napier Field were lucky because the commanding officer there welcomed them. They ate meals in the officers’ mess (dining hall) and lived in the nurses’ d in the nurses’ dormitories. However, officers at some of the other bases resented women pilots and did not welcome them. On some bases, women even had to provide their own places to live.

Adams met her husband while working at Napier Field. One day, just as she was landing, a severe dust storm hit the landing field. A strong crosswind gust caused her plane to nose up and drag a wingtip. Other cadets were trying to land, and she was afraid that because of the poor visibility in the dust storm, one might land on top of her. After the dust had cleared, an officer came to check out her accident. Later she recalled that when she took off her goggles, she  “looked like a clown with two white spots around my eyes and everything else covered with dust.” Things worked out, though, because she later married the officer she met that day on the airstrip. When talking about that stormy day they met, she said, “He was the silver lining in that dark cloud.”

“looked like a clown with two white spots around my eyes and everything else covered with dust.” Things worked out, though, because she later married the officer she met that day on the airstrip. When talking about that stormy day they met, she said, “He was the silver lining in that dark cloud.”

After the war, Adams and her husband, Robert, lived in Houston, Texas, for fifty-four years. When her husband died in 1999, she came back to live in Durham. When asked about her experiences with the WASP, she said, “I loved every second of it.”

In the 1970s, soon after their thirtieth reunion, WASP veterans were very excited to hear that the navy was training a small group of women to be military pilots. But media reports stated that this would be the first time women had flown military aircraft. As Adams said, “The WASP got their stingers out!” Their story had never been told. For thirty years, the government had kept their records sealed, and not many Americans knew of their contributions. So the WASP began to publicize their World War II service. Kate Adams did her part. She gave interviews, spoke to interested groups, and continued to attend annual WASP reunions. Adams also donated her uniform and related photographs to the North Carolina Museum of History. By the time she died in 2002 at the age of eighty-three, the WASP had begun to achieve more public recognition for their service during World War II.

At the time of this article’s publication, Sandra O. Boyd was a media specialist at Lufkin Road Middle School in Apex. She has also served as a volunteer at the North Carolina Museum of History.

Additional Resources:

Women's Air Service Pilots of WWII: http://www.wingsacrossamerica.us/

Women in the U.S. Army: http://www.army.mil/women/pilots.html

NPR, Female WWII Pilots: The Origial Fly Girls: http://www.npr.org/2010/03/09/123773525/female-wwii-pilots-the-original-...

NPR, Women with Wings in WWII: http://www.npr.org/2011/06/01/124367587/wasp-women-with-wings-in-wwii

PBS, Establishment of the WASPS: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/flygirls/peopleevents/pandeAMEX06.html

September 14, 2006. "We Were WASP, part 1." Located at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b3zibVh_NLo&feature=related. Accessed February 28, 2012.

Video & Image Credits

July 8, 2009. "Women Air Service Pilots (WASP) Win Congressional Medal." Located at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GBfaoaAkB7c. Accessed February 28, 2012.

Vaughn, James. January 12, 2012. "WASPs and B-17." Located at https://www.flickr.com/photos/x-ray_delta_one/4270310408/.Accessed February 28, 2012.

1 January 2003 | Boyd, Sandra O.