Great Horned Owl

Bubo virginianus

Written by Wayne Irvin

Contributions to original by Mark E. Johns

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.

Classification

Class: Aves

Order: Strigiformes

Average Size

Length: 18 to 25 in. Males are smaller than females.

Wingspan: 54 in.

Weight: 53 oz.

Food

Mammals up to the size of a woodchuck or skunk; birds up to the size of a Canada goose; any insects; any reptiles or amphibians.

Breeding

Great horned owls are monogamous. They usually choose an old hawk nest in which to lay 2 large, white eggs. Actual breeding is preceded by an interlude of hooting and visual displays between the two owls.

Young

Newly hatched owls are covered with a coat of thick down and are quite weak and helpless for several days. Their eyes open in 7 to 8 days. Both parents feed the young, with one of them constantly at the nest for warmth and defense. Cottontail rabbits are often preferred, but food type depends on hunting habitat. Nestlings require 4 to 6 weeks to achieve maximum size. Plumage development is slower, and the nestlings are approximately 8 to 9 weeks old before they begin to fly.

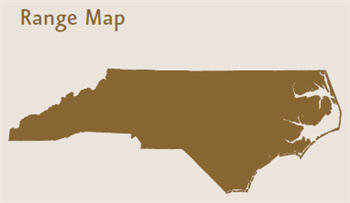

Range and Distribution

The great horned owl inhabits most of the land mass in the Western Hemisphere. It is found from northern Canada to Tierra del Fuego, an archipelago on the southern tip of South America, and in all 100 counties of North Carolina. This bird can be found in just about any type of woodland habitat. It is also found hunting (and even nesting) in city and town limits, farmlands, and suburban areas with scattered trees.

General Information

The great horned owl is the largest owl species in North Carolina. It is found in woodland habitats statewide, including suburbia. The barred owl is also found statewide, but is more typical of swamps, floodplains and moist woodlands. The great horned owl’s closest relative is the eagle owl (Bubo bubo) of Eurasia.

In Birds of North Carolina, T. Gilbert Pearson states that “the great horned owl is the feathered tiger of the air. Like the striped terror of the jungle, it usually hunts by night; among birds and small mammals, it is all powerful and its work of destruction is swift and sure.” This accurately summarizes one of North Carolina’s most efficient avian predators.

Description

The two prominent ear tufts of feathers, resembling horns, give this owl its common name. In North Carolina, the plumage is generally dark reddish brown, heavily streaked or striped over its entire plumage. The wing has feathered edges (especially along the primary feather wind-trailing edges), which dampen sound as the bird flies or glides. Subspecies in the western and northern parts of North America have much grayer plumage. Characteristic of this raptor group, the females of the species are 25 to 30% bigger than the males.

which dampen sound as the bird flies or glides. Subspecies in the western and northern parts of North America have much grayer plumage. Characteristic of this raptor group, the females of the species are 25 to 30% bigger than the males.

These owls have large glaring eyes that are brilliant yellow, giving the animal a cat-like appearance. Like other members of this family, the horned owl’s vision (particularly at night), is exceptional. The huge eyes face forward, giving the animal binocular vision and enabling it to pinpoint prey with deadly accuracy.

Horned owls have an especially keen auditory sense, and the unique construction of owl feathers also enables owls to fly with virtually no sound. This advantage permits owls to approach sharp-eared prey such as rodents and birds, and even small owl species, undetected. It is a myth that owls can turn their heads all the way around but they can turn their heads 180 degrees.

History and Status

The great horned owl is a fairly common species in North Carolina. Mainly nocturnal, great horned owls can occasionally be seen during the day roosting in tall trees. Many people may never have seen a horned owl; however, most have heard their staccato, morse-code hooting: “hoo-hoo, hoo-hoo, hoo-hoo” on cold nights. Most calling occurs when courtship begins in October, with peak calling in November and December, often at dusk and after dark. Calls slow a bit after eggs are in the nest and even more after young have hatched. This is generally the upland counterpart of the barred owl, which is found mostly in bottomland forests.

Despised by rural residents because of their ability to prey successfully on domestic poultry and gamebirds, great horned owls are fully protected by law as are all birds of prey. There are almost no predators of adults, but they may be killed in confrontations with eagles, other great horned owls and the larger snowy owl. (In Harry Potter books, Hedwig is a snowy owl.)

Habitat and Habits

Usually horned owls prefer habitat consisting of wooded ridges with pine, oak and hickory trees, but these birds can be found anyplace where food supplies are plentiful. They are often seen perched on large signs in urban and suburban areas like neighborhoods, college campuses and along roadways. One owl was observed perched on one of the taller office buildings in downtown Raleigh, N.C. during the 1994 Christmas Bird Count! It was probably taking advantage of the abundant domestic pigeons and park squirrels in this concrete-and-asphalt ecosystem. There is no proof great horned owls are declining in number. Although habitat destruction is certainly bad for any species of wildlife, these owls seem to be quite adaptable.

Horned owls are opportunists. They eat almost any protein source they are capable of killing—beetles, as well as waterfowl, small rodents and skunks, porcupines and domestic cats.

These owls rarely construct their own nests. Rather they use old hawk, crow or osprey nests. They will also nest in old gray squirrel leaf nests and on top of a broken-off large tree. Occasionally they even use part of a bald eagle nest while the eagle is still using the nest!

On average, great horned owls lay 2 (sometimes 3) large and oval white eggs, with the female assuming responsibility for the month-long incubation. In North Carolina, owls may lay eggs as early as December; however the average is December-March. Opossums and raccoons eat eggs and young owlets, and both parents vigorously defend the nest. The young are fed small mammals and birds, with cottontail rabbits preferred as food for the young.

When first hatched, the baby owls are covered in gray-white down. The low temperatures make constant brooding by one of the parents necessary. As the young owls reach maturity, the parents cut back on feeding to encourage the adolescents to venture forth and hunt. Only one brood is reared each year.

People Interactions

Owls are quite adaptable and are often attracted to roadside trash near towns and cities. They also hunt for rodents along busy roadsides and may end up being hit and killed by cars. These owls have finally been recognized and appreciated as a control on rodent populations.

NCWRC Interaction: How You Can Help

-

Under federal and state law, it is illegal for anyone to injure, harass, kill or possess a bird of prey or any parts of a bird of prey. This includes harming or removing a nest. If you find an injured owl, contact a licensed wildlife rehabilitator.

-

Great horned owls play an important role in nature as predators of native small animals like rodents. Keep small animals like rabbits, in a pen. Cover chicken pens with wire, and keep small pets inside if an owl has included your property in its night-time hunting range.

-

Owls may suffer from improper pesticide use when they feed on prey that has been exposed to pesticides or feed on other animals that have ingested pesticides. Limit the use of pesticides when possible and always use according to directions on the label.

-

Do not litter along roadways. This draws rodents, and owls can be struck by vehicles as they hunt this common prey.

Links:

To see a video on the great horned owl, go to https://www.nationalgeographic.com/ and enter

great horned owl in the search bar.

References:

Bent, Arthur Cleveland “Great Horned Owl,” in Life Histories of North American Birds of Prey, Part 2 (Dover Publications, 1961), pp. 295-322.

Eckert, Allan and Karl E. Karalus The Owls of North America (Weathervane Books, 1987.)

Potter, Eloise, James F. Parnell and Robert Teulings Birds of the Carolinas (University of North Carolina Press, l980).

Karalus, Karl E. The Owls of North America (Doubleday and Co., 1974).

Credits:

Illustrated by J.T. Newman. Photos by North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.

Produced by the Division of Conservation Education, Cay Cross–Editor.

11 June 2010 | Irvin, Wayne; Johns, Mark E.