White Patriots of North Carolina

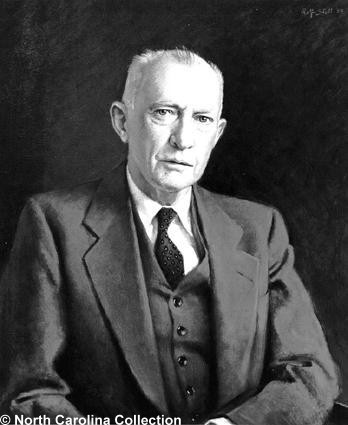

On 22 Aug. 1955, following the U.S. Supreme Court's 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, 356 men and women formed the White Patriots of North Carolina to circumvent the Court's ruling. Made up of mostly lawyers, ministers, professors, teachers, and a few textile magnates and state politicians, the Patriots pledged to maintain "the purity and culture of the white race and of Anglo-Saxon institutions." In addition to white supremacy, they vowed to preserve state rights and promote "friendly racial relations." Led by Wesley Critz George, a University of North Carolina biology professor, John W. Clark, a UNC trustee, and C. L. Shuping, a Greensboro attorney, the Patriots mobilized to frustrate plans to desegregate the North Carolina public schools.

On 22 Aug. 1955, following the U.S. Supreme Court's 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, 356 men and women formed the White Patriots of North Carolina to circumvent the Court's ruling. Made up of mostly lawyers, ministers, professors, teachers, and a few textile magnates and state politicians, the Patriots pledged to maintain "the purity and culture of the white race and of Anglo-Saxon institutions." In addition to white supremacy, they vowed to preserve state rights and promote "friendly racial relations." Led by Wesley Critz George, a University of North Carolina biology professor, John W. Clark, a UNC trustee, and C. L. Shuping, a Greensboro attorney, the Patriots mobilized to frustrate plans to desegregate the North Carolina public schools.

With the help of members from 59 of the state's 100 counties, the White Patriots sent recruitment letters, advertised on the radio and television, and held public meetings to spread their white supremacist message. Members urged white North Carolinians not to let "the negro destroy the white race"; racial mixing, they claimed, would destroy the white race and produce a "mongrel population." Capitalizing on Cold War fears, the Patriots also charged that proponents of desegregation were communists.

In 1956 the White Patriots focused on the Democratic primaries, battling to defeat the three North Carolina congressmen-Thurmond Chatham, Charles Deane, and Harold Cooley-who had refused to sign the Southern Manifesto, a House document opposing the Brown decision. From January to May, the Patriots held mass public meetings in Greensboro, Burlington, Hillsborough, Graham, Asheboro, and Charlotte. Speakers such as state representative Byrd Satterfield and former assistant attorney general I. Beverly Lake asked audiences if they wanted a "white or mulatto posterity," denounced Governor Luther Hodges's passive plan of voluntary segregation, and pilloried Chatham, Deane, and Cooley. Accusing North Carolina of faltering "behind every other state in the South," Satterfield urged North Carolinians to step up their resistance efforts.

As a result of these efforts, two of the three congressmen lost their bid for reelection. Retiring White Patriot president W. C. George later claimed that his organization had inspired North Carolinians to actively oppose integration. Although the Patriots continued to lobby school boards and harass the families of Black children admitted to white schools, their influence waned under the leadership of Troy attorney Horace McCall. Eventually the White Patriots gave way to other white supremacist groups in North Carolina, such as the Defenders of States' Rights.

Reference:

Numan Bartley, The Rise of Massive Resistance: Race and Politics in the South during the 1950s (1969).

Additional Resources:

Christensen, Rob. The Paradox of Tar Heel Politics: The Personalities, Elections, and Events That Shaped Modern North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. 2010. p. 163-164. http://books.google.com/books?id=qkNZo3ZzrhAC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA163#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed September 6, 2012).

Image Credits:

Painting of Wesley Critz George. Image from the Health Sciences Library and North Carolina Collection of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. http://www.hsl.unc.edu/specialcollections/digital/hsl-history/hist21.htm (accessed September 6, 2012).

1 January 2006 | McRae, Elizabeth Gillespie