State of Franklin

In April 1784 the North Carolina legislature ceded the state's western lands to the Continental Congress. On 24 August, soon after news of the Cession Act had reached the west, a convention attended by delegates from Washington, Sullivan, and Greene Counties in the northeast corner of modern Tennessee met at Jonesborough, chose John Sevier as president, and moved toward forming a new state. A second convention in December adopted a provisional constitution for the "State of Franklin" and prefaced it with a declaration of independence from North Carolina. Because of slow communications, the December convention was unaware that in November the North Carolina legislature had rescinded the April Cession Act.

In April 1784 the North Carolina legislature ceded the state's western lands to the Continental Congress. On 24 August, soon after news of the Cession Act had reached the west, a convention attended by delegates from Washington, Sullivan, and Greene Counties in the northeast corner of modern Tennessee met at Jonesborough, chose John Sevier as president, and moved toward forming a new state. A second convention in December adopted a provisional constitution for the "State of Franklin" and prefaced it with a declaration of independence from North Carolina. Because of slow communications, the December convention was unaware that in November the North Carolina legislature had rescinded the April Cession Act.

Separatists in the western counties decided to proceed with their independence movement, and Franklin's first general assembly met in March 1785. It elected Sevier governor and sent a memorial to the Continental Congress requesting admission to the Union. A motion in Congress to approve the cession that would have paved the way for Franklin's statehood fell short of the required nine votes. The struggle over Franklin coincided with the movement to draft a new federal Constitution, and a provision in Article IV of the Constitution prohibited the formation of a state within the jurisdiction of another state without the latter's consent.

The December 1784 constitution of Franklin did not formally define its boundaries. By implication, jurisdiction was assumed over all of the ceded territory, an area approximating the future state of Tennessee. Franklin leaders also hoped to include portions of western Virginia and northern Georgia in the new state.

Residents of North Carolina's western counties were not unanimous in their support of an independent State of Franklin. Settlers in the Cumberland River Valley in Middle Tennessee, which had been set aside as bounty lands for North Carolina's Revolutionary War soldiers, remained aloof from the Franklin movement.

The attitude of North Carolina politicians toward the separatist movement was influenced by their speculation in western lands. Many citizens had obtained vast tracts under the 1783 "Land Grab Act." This law offered for sale all unappropriated land in the Tennessee country, which was soon to be ceded to the United States. Many North Carolina leaders who opposed the cession had not received grants under the 1783 act. Their opportunity to secure title to eastern Tennessee lands was contingent upon the legislature's continued control of the Tennessee land system.

The short history of the Franklin government is an account of Indian war and attempts to gain title to Indian lands, for much of the land claimed by Franklin was occupied by Creeks and Cherokees. John Sevier and other commissioners appointed by the Franklin assembly negotiated the Treaty of Dumplin Creek with several Cherokee chiefs in June 1785. The chiefs ceded to Franklin a tract of land south of the French Broad River within the "Cherokee Reservation," which the North Carolina legislature had set aside in 1783. This area included the site of Greenville, which was to be the capital of Franklin.

The short history of the Franklin government is an account of Indian war and attempts to gain title to Indian lands, for much of the land claimed by Franklin was occupied by Creeks and Cherokees. John Sevier and other commissioners appointed by the Franklin assembly negotiated the Treaty of Dumplin Creek with several Cherokee chiefs in June 1785. The chiefs ceded to Franklin a tract of land south of the French Broad River within the "Cherokee Reservation," which the North Carolina legislature had set aside in 1783. This area included the site of Greenville, which was to be the capital of Franklin.

Efforts to infringe on Indian lands were frustrated by the federal government's determination to maintain peace with the western Indians. The Treaty of Hopewell, signed in November 1785 by commissioners of the Confederation Congress and the Cherokees, nullified both the Treaty of Dumplin Creek and the earlier private purchase of the Muscle Shoals region.

After Richard Caswell became governor of North Carolina in 1784, he followed a conciliatory policy toward the Franklin movement. Evan Shelby, who was appointed brigadier general of the Washington district, was a friend of Sevier, and in the spring of 1787 the two men reached an agreement that granted settlers the choice of paying their taxes to North Carolina or to the State of Franklin. In August 1787 the Franklin assembly elected Shelby to succeed Sevier as governor. Shelby refused the offer but soon resigned as brigadier general and recommended that Sevier be his successor. Sevier's term as governor expired on 1 Mar. 1788, and the legislature did not meet again. The Franklin movement was dead except among settlers in the contested lands south of the French Broad River who had received land titles from the Franklin legislature based on the Treaty of Dumplin Creek. Not until January 1789 did these settlers draft "Articles of Association" and petition North Carolina for protection. In February 1789 John Sevier took an oath of allegiance to North Carolina, and in August he was elected to the North Carolina Assembly.

The "lost" State of Franklin is as entangled in historiographical controversy in the twenty-first century as it was in land speculation, Indian affairs, and political intrigue during its four-year history. It remains a subject of debate whether it originated as a western democratic movement, as a land speculators' conspiracy, or as a separatist movement led by westerners who resented subordination of their interests to those of eastern North Carolina.

References:

Walter Faw Cannon, "Four Interpretations of the History of the State of Franklin," East Tennessee Historical Society Publications 22 (1950).

Noel B. Gerson, Franklin: America's "Lost State" (1968).

Ned Irwin, "The Lost State of Franklin: Sources for Research and Study," Bulletin of Bibliography 55 (March 1998).

Samuel Cole Williams, History of the Lost State of Franklin (rev. ed., 1933).

Additional Resources:

Toomey, Michael. "State of Franklin." Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entry.php?rec=509

Arthur, John Preston. "Chapter VI: The State of Franklin." History of Western North Carolina. Raleigh, N.C.: Edwards and Broughton. 1914. https://archive.org/stream/westernnorthcaro00arth#page/n121/mode/2up

Barksdale, Kevin T. The Lost State of Franklin: America's First Secession. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press. 2009.

Barksdale, Kevin T. "America's First Secession: The Lost State of Franklin Fell Just Short of Admission to the Young Union." The History Channel Magazine. July 2011. p.40-44. http://mds.marshall.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=history_faculty

Ray, Kristofer. “Leadership, Loyalty, and Sovereignty in the Revolutionary American Southwest: The State of Franklin as a Test Case.” The North Carolina Historical Review 92, no. 2 (2015): 123–44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44114500.

"The State of Franklin." Land we love, a monthly magazine devoted to literature, military history, and agriculture. July 1868. p.216-289. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/land-we-love-a-monthly-magazine-devoted-to-literature-military-history-and-agriculture-1868-july-v.5-no.3/501862 (accessed September 19, 2012).

Image Credits:

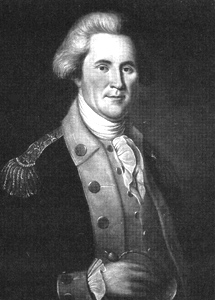

Peale, Charles Willson. Portrait of John Sevier. Image from the Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/image.php?rec=193

The Joseph Purcell map of 1792 showing the boundaries of North Carolina extending to the Mississippi River. Near the center of the state along the western slopes of the Appalachians the map also locates the “New State of Franklin.” North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.

1 January 2006 | Troxler, George W.