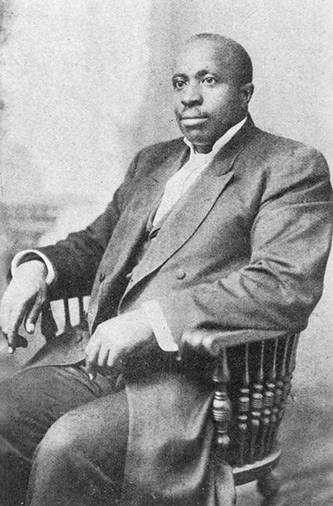

Fuller, Thomas Oscar

25 Oct. 1867–21 June 1942

Thomas Oscar Fuller, state senator, Baptist minister, and educator, was born at Franklinton, the son of J. Henderson Fuller, a house carpenter and wheelwright. Though born into slavery, the elder Fuller taught himself to read; during Reconstruction he was a delegate to Republican conventions and a magistrate, as well as a deacon in the Baptist church. Young Fuller's mother was "Mary Elizabeth."

Thomas Oscar Fuller, state senator, Baptist minister, and educator, was born at Franklinton, the son of J. Henderson Fuller, a house carpenter and wheelwright. Though born into slavery, the elder Fuller taught himself to read; during Reconstruction he was a delegate to Republican conventions and a magistrate, as well as a deacon in the Baptist church. Young Fuller's mother was "Mary Elizabeth."

In 1882, Fuller attended the normal school at Franklinton; its principal, the Reverend Moses A. Hopkins, was later appointed minister to Liberia by Grover Cleveland. Fuller entered Shaw University in 1885, worked his way through college and was graduated with a B.A. degree in 1890. He was soon ordained by the Wake County Baptist Association. His first pastorate was the Belton Creek church at Oxford, held in a log cabin schoolhouse, at a salary of $50 a year. Fuller also taught at a public school in Granville County for $30 a month. In 1892, he returned to Franklinton to form and run a "colored graded" school, subsequently known as the Girls Training School. Two years later he became principal of the Shiloh Institute at Warrenton.

Politically this section of the state was strongly "colored Republican," for many Black politicians held office in the party hierarchy. When in 1898 Charles A. Cooke, a white Republican representing the Eleventh District (Warren and Vance counties), had to relinquish his nomination for the senate, it was offered to Fuller, who accepted with hesitation but won the election without difficulty. The reasons for the misgivings he had entertained soon surfaced, primarily due to inflammatory cries of white supremacy and Black domination. Nevertheless, though the only African-American in the senate, Fuller achieved several objectives. He was largely responsible for getting the circuit court to hold hearings every four months instead of every six, thus easing the confinement terms of arrested persons and reducing the docket. He persuaded the senate not to reduce the number of Black normal schools from seven to four. He also supported publication of sketches of North Carolina regiments in the Civil War, but contended that credit should be given to "those who stayed home and raised cotton and corn."

In 1899, the Democratic party pushed its constitutional amendment to disfranchise Black citizens. In debate, Senator Fuller took the floor and in an impassioned speech argued against the proposal, stating among other things that Black domination was unlikely with 210,000 white to 125,000 Black votes. According to the press, "He was one of the most fluent speakers of the convention. He swept the audience away on wings of oratory." Nevertheless, the amendment, including the Grandfather Clause, passed 42 to 6.

In November 1900, Fuller accepted a call to the First Baptist Church at 217 Beale Street in Memphis, Tenn. There he found a splinter group with only $100 in assets and a rented hall. A born organizer and persuader, he soon increased the size of the congregation and embarked on a building program. (In later years a second church was erected on St. Paul's Avenue and still later, in 1941, a new church was built at Lauderdale and Polk streets.)

In 1902, Fuller was appointed principal of Howe Institute, which subsequently merged with Roger Williams College, where he held classes in theology for local pastors. Howe was a training school to give young Black people—soon men and women—manual skills as well as exposure to academic and cultural subjects, including Latin and Greek. With Fuller's drive and with active support from northern Baptists, the building was enlarged, growing fivefold in value in the next ten years.

In 1906, Fuller received a doctor of philosophy degree from the Agriculture and Mechanical College of Normal, Ala. Shaw University awarded him an M.A. in 1908 and a doctor of divinity degree in 1910. He gave the invocation at a ceremony when President Theodore Roosevelt visited Memphis in conjunction with the Philippine governor, Luke Wright, a former Confederate soldier and native of the city. Hopes that Roosevelt might name Fuller as minister to Liberia were not fulfilled, somewhat to Fuller's relief.

He was married four times: to Lucy G. Lewis of Franklinton; to Laura Faulkner, mother of Thomas and Erskin; to a woman named Rosa; and to Dixie Williams. Thomas Fuller, Jr., was the only one of his children to reach adulthood.

Fuller died in Memphis and was buried at New Park Cemetery. Notables from the city, county, and state as well as leading Baptists attended the funeral. One Baptist leader remarked that Dr. Fuller had fulfilled the four requirements for distinction needed by a man. He had left a son, built a house, planted a tree, and written a book. He was the author of Flashes and Gems (1920); Pictorial History of the American Negro (1933); History of Negro Baptists in Tennessee (1936); Bridging the Racial Chasm (1937); Story of Church Life Among Negroes (1938); and Notes on Parliamentary Law (1940).

References:

Thomas O. Fuller, Twenty Years in Public Life (1910).

Fuller's correspondence with family members and others (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill).

William Hartshorn, An Era of Progress and Promise (1910).

National Baptist Publishing House (1910).

National Baptist Voice 24 (15 July 1942 [portrait]).

Raleigh News and Observer, 30 Nov. 1941.

Additional Resources:

Van West, Carroll, and Jen Stoecker, "Thomas Oscar Fuller." Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture version 2.0. Tennessee Historical Society. http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entry.php?rec=528

Starnes, Richard D. "Fuller, Thomas Oscar." Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Oxford University Press. 2005. Second edition. 732-733. http://books.google.com/books?id=TMZMAgAAQBAJ&pg=RA1-PA732#v=onepage&q&f=false

Bacote, Samuel William, editor. "Reverend Thomas O. Fuller A.M., Ph.D." Who's who among the colored Baptists of the United States. Kansas City, Mo.: Franklin Hudson Publishing Co. 1913. 121-123 https://archive.org/stream/whoswhoamongcolo00baco#page/120/mode/2up

"T.O. Fuller State Park." Tennessee State Parks. Tennessee Department of Environment & Conservation. http://tnstateparks.com/parks/about/t-o-fuller

Image Credits:

"Thomas O. Fuller." Photograph. Twenty years in public life, 1890-1910, North Carolina-Tennessee. Nashville, Tenn: National Baptist Publishing Board. 1910. Schomburg Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division. New York Public Library Digital Gallery. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dd-e883-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 (accessed March 12, 2014).

1 January 1986 | Macfie, John